2008-03-05

For greater security-critical behaviour in Europe

A proposal for the resistance movement: Against NATO, G8 and swedish EU Presidency 2009

Each protest enables us to draw conclusions of how to do things better next time. In the same way, we can draw conclusions from the mobilisation against the G8 summit 2007 in Heiligendamm on how to achieve successful and broad resistance. Apart from three large self-organised protest camps and an international infotour in the months leading up to the summit, there were attempts to have international exchanges and establish networks beyond Germany. The decision was made not to respond to the G8 climate debate but to frame the protests in terms of other self-determined topics the movement was focussing on: migration, antimilitarism and global agriculture.

Looking ahead to the 60th NATO anniversary in Strasbourg and Kehl and the G8 2009 in Italy, but also to the swedish EU Presidency 2009, this text takes up these points to propose a campaign against the new “European Security Architecture”. We outline some developments in police cooperation on a European level and call for a kind of antirepression work that goes beyond a simple critique and a scandalising police violence, and that is coordinated on a European level. Such political antirepression work would have to take new forms of social control seriously as an integral reference point for radical movements.

No future for freedom

At the latest since September 11th 2001, not only the foreign policy coordinates of the European Union (EU) have changed. Under the motto “Terror Comes Home”, far-reaching changes in European Home Affairs, along with police operations towards a “preventive security state” have been implemented. Whilst control of the external EU border has been stepped up with new technologies and cross-border cooperation, surveillance and control within the EU is also steadily increasing. Additionally, there are foreign military and police operations on behalf of the EU in so-called “third countries”. The EU intends to be a model for a security complex that can be exported to other countries in the EU’s capacity as a “service provider”. These developments are not only directed at migrants and “security-critical” behavior. They also offer a welcome opportunity to control the re-emerging alterglobalisation movement.

Since 1999, the EU has defined Europe as a “space of freedom, security and law”. In future there will be more juridical and police cooperation in criminal and civil affairs. Home Affairs ministers dream of an EU ministry for Home Affairs. On the police level, EU bodies have received more competences, and new institutions and programmes have come into existence. In 2007, the so-called “Future Group” met for the first time. This group is made up of the ministers of Home Affairs of the countries due to hold the EU presidency in the next four years. The EU commissioner for “freedom, security and law” is also part of this group, along with the director of the “Border Protection Agency” Frontex. The Future Group calls itself “informal”, but it has considerable influence on Home Affairs with respect to the EU Treaty as well the 2007 Lissabon negotiations. The foundation of the Future Group coincided with the EU presidency of Germany in 2007. Under the motto “Living a secure Europe”, the German Home Affairs Minister successfully pushed through a tightening of European internal policies1.

Cross-border cooperation

Until now, cross-border police cooperation has only existed between some countries under the Pruem Treaty. This found its expression, for example, during the G8 summit 2003 when German police participated in an operation against demonstrators in Geneva with 500 police officers and five water canons. The Pruem Treaty was a test case and has subsequently been integrated in the “legal framework of the EU”. Thus it now applies to all EU countries. All police departments will now have access to DNA and fingerprint databases as well as vehicle registration data. Access to information on “terrorism suspects and travelling violent criminals” will be made easier in order to prevent travel or to “quickly recognise and detain rioters”. For the European Football Championship in 2008, 2 000 German police officers have been ordered from Austria and Switzerland.

As an intersection for police cooperation, the competencies of Europol in The Hague are not restricted to gathering data and advising police forces of EU member states. An EU parliamentary decision in January 2008 meant that the “European Police Office” became an EU agency for the “coordination, organisation and implementation of investigative and operational measures”. The realms of responsibility have been extended to “organised crime” and “other forms of serious crime”. In future, access to the “Europol Information System” will not require a “liaison officer” anymore.

These “liaison officers” are sent by the police forces of all member states to European control and decision-making bodies and are key figures in the policing of major events. Officially they have an “advisory function”. In practice, they function as important nodes in informal police cooperation. They have access to all the databases of their home countries and can, for example during summit protests, provide information about different political groups. Liaison officers coordinate entry restrictions which led to 600 people being denied entry into Germany during the G8 2007, because they had been “conspicuous during previous G8 summits”.

Europe – a space of surveillance and control

The cooperation between police and intelligence services is being expanded. In Germany, the Federal Criminal Investigation Office and the “Verfassungsschutz” (Office for the Protection of the Constitution) recently moved to a “Joint Terrorism Defence Centre”, where they have separate offices but meet daily for joint briefings and share the canteen space. This cooperation led to the surveillance of the anti-g8-movement and the start of investigative operations under the premise of terrorism suspicions. German terrorism legislation allows for far-reaching interferences in people’s privacy and allowed a record to be taken of all mobile phone numbers present at a meeting of the radical left dissent!-network against the G8. As people affected by these operations have been able to access their files, it has come to light that these investigations were carried out by the police but initiated by the intelligence services.

Internet surveillance has increased across Europe. The German Ministry for Home Affairs has started a European-wide initiative to fight “international terrorism”, entitled “check the web”. On March 8th 2007, Europol’s “information portal” went live. German police and secret services intend to cooperate with a joint “internet monitoring and analysis project” in the future. Such “internet surveillance centres” are planned across Europe. The intention is to partially automatise the monitoring of websites and subsequent archiving in police databases. New software scans the databases to find “entities”, which are conceptual analogies or connections between persons and objects (“semantic technologies”). The security industry is developing programmes that are able to search in different file formats. This way, text, audio, video and gps data can be analysed together. Prosecution agencies of various countries already use software that enables the “prediction of crimes” as a result of data analysis. One company describes this process as an “evolution in fighting crime”.

More police repression and law enforcement can also be observed in other countries of Europe. In Italy, several trials in relation to the G8 2001, as well as demonstrations against militarism and fascism concluded with sentences between 6 and 12 years for the accused. In other countries, police laws are being changed in order to give police more powers against “security-critical behaviour”.

Radical changes have been made in Europe under Sarkozy and Berlusconi. In France, passengers who are the first to stand up to protest against a deportation on their flight risk being charged with ringleadership. New legislation in Italy has allocated 2,500 military troops for assistance in police operations to “maintain public order”. The police intend to fingerprint any children of Roma origin found unaccompanied in the streets.

The new Austrian legislation on security police makes the racist control of migrants easier. The German Federal Police now have more competencies both for missions abroad and for domestic affairs, for example against political protests. EU member states implement European directives and “harmonise” their national legislations, for example with respect to data retention. Telecommunication and internet providers now have to store data and hand it over to the police on request. This enables the police to reconstruct communications and create “relational diagrams”. Protection from surveillance is increasingly restricted. The users of encryption software in Austria and the UK should be obliged to give the police their passwords. Home affairs ministers are currently conducting a centralisation of all European police databases.

Institutions and research programs of the European security architecture

In order to have more control over mass protest, for example during G8 summits, new institutions and research programmes have been developed. European police forces conduct joint trainings and maneuvers to control demonstrations. In European police academies operational tactics for “crowd management” are designed. The European Police Academy (CEPOL), based in Hampshire, UK plays a crucial role: “CEPOL’s mission is to bring together senior police officers from police forces across Europe – essentially to support the development of a network – and encourage cross-border cooperation in the fight against crime, public security and law and order, by organising training activities and research findings”.

Following the summit protests in Genoa and Gothenburg in 2001, in 2004 the EU initiated the research programme, “Coordinating National Research Programmes on Security during Major Events in Europe” (EU-SEC). EU-SEC coordinates police departments of EU member states and Europol and publishes a handbook for summit protests. Police are advised to observe protest movements, to exchange data, to enforce travel bans, and to undertake aggressive media strategies in order to delegitimise resistance. In the form of questionnaires, information is gathered about European groups and individuals, their action forms, websites, mail addresses, international contacts, preferred travel routes, means of transport and accommodation.

EU-SEC is coordinated by the UN working group “International Permanent Observatory on Security during Major Events” (IPO), based in the Italian city Turin. IPO advises governments on the appropriate security architecture for major events. IPO services are free. At the moment, IPO is putting together a “Handbook for G8 states”. Official operational areas since its foundation in 2006 have so far been the G8 summits in St Petersburg and Heiligendamm, the World Bank/IMF summit in Singapore, and the Asia-pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting in Vietnam. Also, the Olympic Games 2008 in Beijing and the G8 summit 2008 in Japan were coached by IPO.

Border control: the militarisation of migration control

With the extension of the EU member states and the abolition of border controls, the new external EU borders are being technically upgraded. They include nightview technology, automatic analysis of video surveillance and high frequency cables that can measure and communicate the water concentration of nearby bodies. New joint headquarters have come into existence. Through the extension of the Schengen Information System II (SIS II), more data is available to police forces. Fingerprints and biometrical data of migrants are to be stored in the Visa Information System (VIS). Home affairs ministers complain about the insufficient police control of migrants and have demanded the use of RFID chips (chips with radio waves) in passports. These chips could, for example, acoustically identify the bearers of an expired visa, without this person actually having to show his/her passport.

With the creation of the “Border Control Agency Frontex” in Warsaw, EU-wide “migration control” now has another pillar.The General Director, Ilkha Laitinen, a Finnish border officer, summarises the “Integrated Border Management” of Frontex in the following way, “All those who don’t deserve to be and whom one does not want to have on one’s territory, have to be stopped.” In a “risk analysis center” prognoses of waves of migration are undertaken, information is passed to the relevant border police departments and concrete measures are “recommended”. Frontex has a “central technical toolbox” for member states’ control and surveillance of external borders. Frontex conducts operations together with national police forces (“Frontex Joint Support Teams”). Although Frontex has no forces of its own to fight migration, there has been an extensive increase in the arsenal of border forces of member states. The Italian Carabinieri for instance have new boats, helicopters and surveillance technology. According to its own publications, 115 boats, 27 helicopters, and 21 aeroplanes are documented in the central register of Frontex. Besides trainings, Frontex also undertakes research programs. For example, they research and recommend the use of “micro-helicopters” for border observation. Director Laitinen has expressed his wish for Frontex to have more of its own resources and operative forces in the future.

Police and combatting counter-insurgency abroad

The Lissabon Treaty also addresses “reforms” in the field of military affairs. The “European Security and Defense Policy” asks for a “gradual improvement of military capacities”. The Lissabon Treaty also plans “reforms” within the field of military politics. The aim os for the EU to have armed units at its disposal by 2010. In January 2007 the first EU Battlegroup was declared fully operational; in 2006 such a unit was already considerably involved in the EU military deployment in Congo. There are also means for intervention in “third states” that are much less visible: The “European Gendarmerie Forces” (EGF). The EGF is a paramilitary police unit founded and developed at the G8 summits in 2002 and 2004. It should be able to mobilise 3 000 police officers within 4 weeks. Forces are so far provided by the Netherlands, France, Spain, Italy and Portugal. The EGF is supposed to take over police control after military deployments in crisis areas, as well as ensure “public order” during the “occurrence of public unrests”. The non-domestic deployment of police forces is considered a “civilian instrument”. So far, maintaining “public order” in “third states” has been the task of the military, although it always has cooperated with police units. For example in Bosnia, members of the German Army were trained by Italian Carabinieri. The official tasks of the EGF include “the entire spectrum of police deployments, civilian authority and military command, control of local police authorities, criminal investigation activities, activities for the provision of secret intelligence, property protection” etc. The statute of the EGF does not exclude a deployment within the EU. The headquarters of the EGF are located in the Italian city of Vicenza at a Carabinieri base. Likewise, in Vicenza the EGF have their own academy (COESPU) where their own forces as well as units of other countries are trained. The academy is financed by the G8 states. Also, senior police officers of Pakistan and Kenya have undergone COEPSU training in “riot control”.

The significance for radical movements

“The distinction between international law in times of peace and in times of war is no longer appropriate in the face of new threats”, Schäuble, the German Minister of Home Affairs has stated. The German chancellor and the head of the Federal Criminal Investigation police have further conceded that, “the separation between internal and external security is obsolete”. What do these developments mean for the political practice of radical movements in general and for the alterglobalisation movement specifically, except “even more repression”? A debate about repression should be an integral part of the practice of radical movements. It is clear that the margins for left interventions have not increased in light of and after 9/11. Nonetheless, we think that it is not only the speed and the degree of repressive measures that has changed. The entire social matrix within which radical left politics is situated is shifting. The quality of surveillance and social control has taken on another form. Apart from technological developments, above all this has to do with the transnational coordination of control agencies and the “interdependency of internal and external security”.

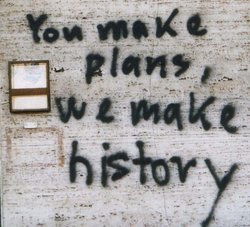

But we see an opportunity in using this continued narrowing of the freedom of movement as a chance to build new alliances that will bring about broad social debates and unexpected interventions. A conjunction of classical antimilitarism, antirepression, and migration politics is a clear option. The degree to which these new measures and institutions touch upon the daily life of every European should offer sufficient starting points for a practice of proactive disobedience against this evolving European Security Architecture.

Against the European Security Architecture

The decision to mark the 60th anniversary of NATO with jointly hosted celebrations in Strasbourg (France) and Kehl (Germany) has already caused a great deal of activity amongst the antimilitarist left in a number of countries in Europe. The established peace movements in France and Germany plan to focus their protests on the Afghanistan war. However, the NATO summit would also be an excellent opportunity to draw attention to the complex structure of the “global security architecture” with its participating institutions. Military and police forces currently maintain a repertoire of repressive instruments based on new technological developments. Computer-supported commandos, investigative software, warmth and body fluid detectors at national borders, tasers etc. Military and police remits are being ever more synchronised, both on a legislative basis and through joint operations, but also with the creation of common organisations such as the “European Gendarmerie Force” based in Vicenza. "Eurocorps, the French Foreign Legion and the central Schengen Information System are all located in Strasbourg, where next year’s NATO conference is to be held. These facts provide ample reasons for an anti-NATO mobilisation to focus on developing a radical critique of the militarisation of social conflict within the EU and beyond.

The G8 in Italy provides an opportunity to raise public awareness about and criticise the international police coordination against summit protests. Some of the measures and institutions have been installed under the direction of Frattini, the former EU Commissioner for Justice, Freedom and Security, now foreign minister under Berlusconi. The EU-SEC programme against mass political protests was initiated after the G8 in Genoa. The UN initiative “International Permanent Observatory on Security during Major Events” is being coordinated from Turin. We can assume that after the experiences of the G8 2001, the G8 2009 will be a matter of prestige for all of these agencies. Their preparations for the G8 2009 have probably already begun.

A decision by Italian social movements to focus on militarism as a prominent mobilisation issue against the G8 2009 could combine the critique of militarised foreign politics with resistance to the new coordinates of European domestic politics. Resistance against the “policialisation of internal and external security” could connect with the movement against the NATO basement Dal Molin in the Italian city Vicenza. A protest movement that has mobilised for several major demonstrations against the extension of the basement has been active there for several years. As the seat of the European Gendarmery Forces, Vicenza could become the symbol of resistance to the paramilitary organisation of European police forces. Moreover, after the Kosovan declaration of independence, “Eulex”, the biggest EU police mission with 2 000 officers, mainly from Germany and Italy, was established. 700 of them are designated for deployment during demonstrations. On the Italian side, this task will probably be taken over by the Carabinieri units of the EGF. “Eulex” supports the NATO KFOR troops in Kosovo in maintaining “public order”, which thus combines a military with a “civil” intervention.

In 2009, the EU Commission’s “Hague Programme for Freedom, Security and Justice” will draw to a close. Changes and targets for a “European Security Architecture” will be codified in a new 5 year programme under the Swedish EU presidency. European police cooperation, Europol, Eurojust and Frontex will be optimised and made more efficient. “COSI”, a “Standing Committee on Internal Security” within the European Council will pave the way for interior ministers to create an overarching EU Interior Ministry.

We propose to use the European Social Forums (ESF) and other summit mobilizations as one of the moments for the European coordination between groups working on police issues, antirepression initiatives, and supportive lawyers/legal activists. Internal policy developments concerning surveillance and control in Europe could be brought together there. We would be interested in finding out where resistance to the “European Security Architecture” already exists. How are demands formulated and publicly articulated in other countries? How do activists relate to discourses on fundamental rights and civil liberties? Connecting to these practices we could start looking for common perspectives and, sooner or later, collapse the “European security architecture”.

This text should be understood as a first outline of a contribution to the international “Summer of Resistance” 2009. We look forward to more English reports, position papers and discussions. We can be reached under euro-police [at] so36.net.

Activists from Gipfelsoli | Prozessbeobachtungsgruppe Rostock | MediaG8way

1 “Europa sicher leben | Living Europe Safely | L’Europe, bien sûr(e)”: http://euro-police.noblogs.org/gallery/3874/Europa_sicher_leben.pdf