The 2008 G-8 in Hokkaido, a Strategic Assessment

Bristol, Mayday, 2008

zero

The authors of this document are a collection of activists, scholars, and

writers currently based in the United States and Western Europe who have

gotten to know and work with each other in the movement against capitalist

globalization. We’re writing this at the request of some members of No! G8

Action Japan, who asked us for a broad strategic analysis of the state of

struggle as we see it, and particularly, of the role of the G8, what it

represents, the dangers and opportunities that may lie hidden in the moment.

It is in no sense programmatic. Mainly, it is an attempt to develop tools

that we hope will be helpful for organizers, or for anyone engaged in the

struggle against global capital.

I

It is our condition as human beings that we produce our lives in common.

II

Let us then try to see the world from the perspective of the planet’s

commoners, taking the word in that sense: those whose most essential

tradition is cooperation in the making and maintenance of human social life,

yet who have had to do so under conditions of suffering and separation;

deprived, ignored, devalued, divided into hierarchies, pitted against each

other for our very physical survival. In one sense we are all commoners. But

it’s equally true that just about everyone, at least in some ways, at some

points, plays the role of the rulers‹of those who expropriate, devalue and

divide‹or at the very least benefits from such divisions.

Obviously some do more than others. It is at the peak of this pyramid that

we encounter groups like the G8.

III

The G8’s perspective is that of the aristocrats, the rulers: those who

command and maintain that global machinery of violence that defends existing

borders and lines of separation: whether national borders with their

detention camps for migrants, or property regimes, with their prisons for

the poor. They live by constantly claiming title to the products of others

collective creativity and labour, and in thus doing they create the poor;

they create scarcity in the midst of plenty, and divide us on a daily basis;

they create financial districts that loot resources from across the world,

and in thus doing they turn the spirit of human creativity into a spiritual

desert; close or privatize parks, public water taps and libraries,

hospitals, youth centers, universities, schools, public swimming pools, and

instead endlessly build shopping malls that channels convivial life into a

means of commodity circulation; work toward turning global ecological

catastrophe into business opportunities.

These are the people who presume to speak in the name of the ‘international

community’ even as they hide in their gated communities or meet protected by

phalanxes of riot cops. It is critical to bear in mind that the ultimate aim

of their policies is never to create community but to introduce and maintain

divisions that set common people at each other’s throats. The neoliberal

project, which has been their main instrument for doing so for the last

three decades, is premised on a constant effort either to uproot or destroy

any communal or democratic system whereby ordinary people govern their own

affairs or maintain common resources for the common good, or, to reorganize

each tiny remaining commons as an isolated node in a market system in which

livelihood is never guaranteed, where the gain of one community must

necessarily be at the expense of others. Insofar as they are willing to

appeal to high-minded principles of common humanity, and encourage global

cooperation, only and exactly to the extent that is required to maintain

this system of universal competition.

IV

At the present time, the G8‹the annual summit of the leaders of ‘industrial

democracies’‹is the key coordinative institution charged with the task of

maintaining this neoliberal project, or of reforming it, revising it,

adapting it to the changing condition of planetary class relations. The role

of the G8 has always been to define the broad strategic horizons through

which the next wave of planetary capital accumulation can occur. This means

that its main task is to answer the question of how 3Ž4 in the present

conditions of multiple crises and struggles 3Ž4 to subordinate social

relations among the producing commoners of the planet to capital’s supreme

value: profit.

V

Originally founded as the G7 in 1975 as a means of coordinating financial

strategies for dealing with the ‘70s energy crisis, then expanded after the

end of the Cold War to include Russia, its currently face a moment of

profound impasse in the governance of planetary class relations: the

greatest since the ‘70s energy crisis itself.

VI

The ‘70s energy crisis represented the final death-pangs of what might be

termed the Cold War settlement, shattered by a quarter century of popular

struggle. It’s worth returning briefly to this history.

The geopolitical arrangements put in place after World War II were above all

designed to forestall the threat of revolution. In the immediate wake of the

war, not only did much of the world lie in ruins, most of world’s population

had abandoned any assumption about the inevitability of existing social

arrangements. The advent of the Cold War had the effect of boxing movements

for social change into a bipolar straightjacket. On the one hand, the former

Allied and Axis powers that were later to unite in the G7 (the US, Canada,

UK, France, Italy, Germany, Japan)‹the ‘industrialized democracies’, as they

like to call themselves‹engaged in a massive project of co-optation. Their

governments continued the process, begun in the ‘30s, of taking over social

welfare institutions that had originally been created by popular movements

(from insurance schemes to public libraries), even to expand them, on

condition that they now be managed by state-appointed bureaucracies rather

than by those who used them, buying off unions and the working classes more

generally with policies meant to guarantee high wages, job security and the

promise of educational advance‹all in exchange for political loyalty,

productivity increases and wage divisions within national and planetary

working class itself. The Sino-Soviet bloc‹which effectively became a kind

of junior partner within the overall power structure, and its allies

remained to trap revolutionary energies into the task of reproducing similar

bureaucracies elsewhere. Both the US and USSR secured their dominance after

the war by refusing to demobilize, instead locking the planet in a permanent

threat of nuclear annihilation, a terrible vision of absolute cosmic power.

VII

Almost immediately, though, this arrangement was challenged by a series of

revolts from those whose work was required to maintain the system, but who

were, effectively, left outside the deal: first, peasants and the urban poor

in the colonies and former colonies of the Global South, next,

disenfranchised minorities in the home countries (in the US, the Civil

Rights movement, then Black Power), and finally and most significantly, by

the explosion of the women’s movement of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s‹the

revolt of that majority of humanity whose largely unremunerated labor made

the very existence ‘the economy’ possible. This appears to have been the

tipping point.

VIII

The problem was that the Cold War settlement was never meant to include

everyone. It by definition couldn’t. Once matters reached tipping point,

then, the rulers scotched the settlement. All deals were off. The oil shock

was first edge of the counter-offensive, breaking the back of existing

working class organizations, driving home the message that there was nothing

guaranteed about prosperity. Under the aegis of the newly hatched G7, this

counter-offensive involved a series of interwoven strategies that were later

to give rise to what is known as neoliberalism.

IX

These strategies resulted in what came to be known as ‘Structural

Adjustment’ both in the North and in the South, accompanied by trade and

financial liberalization. This, in turn, made possible crucial structural

changes in our planetary production in common extending the role of the

market to discipline our lives and divide us into more and more polarized

wage hierarchy. This involved:

• In the immediate wake of ‘70s oil shock, petrodollars were recycled

from OPEC into Northern banks that then lent them, at extortionate rates of

interest, to developing countries of the Global South. This was the origin

of the famous ‘Third World Debt Crisis.’ The existence of this debt allowed

institutions like the IMF to impose its monetarist orthodoxy on most of the

planet for roughly twenty years, in the process, stripping away most of even

those modest social protections that had been won by the world’s poor‹large

numbers of whom were plunged into a situation of absolute desperation.

• It also opened a period of new enclosures through the capitalist

imposition of structural adjustment policies, manipulation of environmental

and social catastrophes like war, or for that matter through the

authoritarian dictates of ‘socialist’ regimes. Through such means, large

sections of the world’s population have over the past thirty years been

dispossessed from resources previously held in common, either by dint of

long traditions, or as the fruits of past struggles and past settlements.

• Through financial deregulation and trade liberalization, neoliberal

capital, which emerged from the G7 strategies to deal with the 1970s crisis

aimed thus at turning the ‘class war’ in communities, factories, offices,

streets and fields against the engine of competition, into a planetary

‘civil war’, pitting each community of commoners against every other

community of commoners.

• Neoliberal capital has done this by imposing an ethos of ‘efficiency’

and rhetoric of ‘lowering the costs of production’ applied so broadly that

mechanisms of competition have come to pervade every sphere of life. In fact

these terms are euphemisms, for a more fundamental demand: that capital be

exempt from taking any reduction in profit to finance the costs of

reproduction of human bodies and their social and natural environments

(which it does not count as costs) and which are, effectively, ‘exernalized’

onto communities and nature.

• The enclosure of resources and entitlements won in previous

generations of struggles both in the North and the South, in turn, created

the conditions for increasing the wage hierarchies (both global and local),

by which commoners work for capital‹wage hierarchies reproduced economically

through pervasive competition, but culturally, through male dominance,

xenophobia and racism. These wage gaps, in turn, made it possible to reduce

the value of Northern workers’ labour power, by introducing commodities that

enter in their wage basket at a fraction of what their cost might otherwise

have been. The planetary expansion of sweatshops means that American workers

(for example) can buy cargo pants or lawn-mowers made in Cambodia at

Walmart, or buy tomatoes grown by undocumented Mexican workers in

California, or even, in many cases, hire Jamaican or Filipina nurses to take

care of children and aged grandparents at such low prices, that their

employers have been able to lower real wages without pushing most of them

into penury. In the South, meanwhile, this situation has made it possible to

discipline new masses of workers into factories and assembly lines, fields

and offices, thus extending enormously capital’s reach in defining the

terms‹the what, the how, the how much‹of social production.

• These different forms of enclosures, both North and South, mean that

commoners have become increasingly dependent on the market to reproduce

their livelihoods, with less power to resist the violence and arrogance of

those whose priorities is only to seek profit, less power to set a limit to

the market discipline running their lives, more prone to turn against one

another in wars with other commoners who share the same pressures of having

to run the same competitive race, but not the same rights and the same

access to the wage. All this has meant a generalized state of precarity,

where nothing can be taken for granted.

X

In turn, this manipulation of currency and commodity flows constituting

neoliberal globalization became the basis for the creation of the planet’s

first genuine global bureaucracy.

• This was multi-tiered, with finance capital at the peak, then the

ever-expanding trade bureaucracies (IMF, WTO, EU, World Bank, etc), then

transnational corporations, and finally, the endless varieties of NGOs that

proliferated throughout the period‹almost all of which shared the same

neoliberal orthodoxy, even as they substituted themselves for social welfare

functions once reserved for states.

• The existence of this overarching apparatus, in turn, allowed poorer

countries previously under the control of authoritarian regimes beholden to

one or another side in the Cold War to adopt ‘democratic’ forms of

government. This did allow a restoration of formal civil liberties, but very

little that could really merit the name of democracy (the rule of the

‘demos’, i.e., of the commoners). They were in fact constitutional

republics, and the overwhelming trend during the period was to strip

legislatures, that branch of government most open to popular pressure, of

most of their powers, which were increasingly shifted to the executive and

judicial branches, even as these latter, in turn, largely ended up enacting

policies developed overseas, by global bureaucrats.

• This entire bureaucratic arrangement was justified, paradoxically

enough, by an ideology of extreme individualism. On the level of ideas,

neoliberalism relied on a systematic cooptation of the themes of popular

struggle of the ‘60s: autonomy, pleasure, personal liberation, the rejection

of all forms of bureaucratic control and authority. All these were

repackaged as the very essence of capitalism, and the market reframed as a

revolutionary force of liberation.

• The entire arrangement, in turn, was made possible by a preemptive

attitude towards popular struggle. The breaking of unions and retreat of

mass social movements from the late ‘70s onwards was only made possible by a

massive shift of state resources into the machinery of violence: armies,

prisons and police (secret and otherwise) and an endless variety of private

‘security services’, all with their attendant propaganda machines, which

tended to increase even as other forms of social spending were cut back,

among other things absorbing increasing portions of the former proletariat,

making the security apparatus an increasingly large proportion of total

social spending. This approach has been very successful in holding back mass

opposition to capital in much of the world (especially West Europe and North

America), and above all, in making it possible to argue there are no viable

alternatives. But in doing so, has created strains on the system so profound

it threatens to undermine it entirely

XI

The latter point deserves elaboration. The element of force is, on any

number of levels, the weak point of the system. This is not only on the

constitutional level, where the question of how to integrate the emerging

global bureaucratic apparatus, and existing military arrangements, has never

been resolved. It is above all an economic problem. It is quite clear that

the maintenance of elaborate security machinery is an absolute imperative of

neoliberalism. One need only observe what happened with the collapse of the

Soviet bloc in Eastern Europe: where one might have expected the Cold War

victors to demand the dismantling of the army, secret police and secret

prisons, and to maintain and develop the existing industrial base, in fact,

what they did was absolutely the opposite: in fact, the only part of the

industrial base that has managed fully to maintain itself has been the parts

required to maintained the security apparatus itself! Critical too is the

element of preemption: the governing classes in North America, for example,

are willing to go to almost unimaginable lengths to ensure social movements

never feel they are accomplishing anything. The current Gulf War is an

excellent example: US military operations appear to be organized first and

foremost to be protest-proof, to ensure that what happened in Vietnam (mass

mobilization at home, widespread revolt within the army overseas) could

never be repeated. This means above all that US casualties must always be

kept to a minimum. The result are rules of engagement, and practices like

the use of air power within cities ostensibly already controlled by

occupation forces, so obviously guaranteed to maximize the killing of

innocents and galvanizing hatred against the occupiers that they ensure the

war itself cannot be won. Yet this approach can be taken as the very

paradigm for neoliberal security regimes. Consider security arrangements

around trade summits, where police are so determined prevent protestors from

achieving tactical victories that they are often willing to effectively shut

down the summits themselves. So too in overall strategy. In North America,

such enormous resources are poured into the apparatus of repression,

militarization, and propaganda that class struggle, labor action, mass

movements seem to disappear entirely. It is thus possible to claim we have

entered a new age where old conflicts are irrelevant. This is tremendously

demoralizing of course for opponents of the system; but those running the

system seem to find that demoralization so essential they don’t seem to care

that the resultant apparatus (police, prisons, military, etc) is,

effectively, sinking the entire US economy under its dead weight.

XII

The current crisis is not primarily geopolitical in nature. It is a crisis

of neoliberalism itself. But it takes place against the backdrop of profound

geopolitical realignments. The decline of North American power, both

economic and geopolitical has been accompanied by the rise of Northeast Asia

(and to a increasing extent, South Asia as well). While the Northeast Asian

region is still divided by painful Cold War cleavages‹the fortified lines

across the Taiwan straits and at the 38th parallel in KoreaŠ‹the sheer

realities of economic entanglement can be expected to lead to a gradual

easing of tensions and a rise to global hegemony, as the region becomes the

new center of gravity of the global economy, of the creation of new science

and technology, ultimately, of political and military power. This may, quite

likely, be a gradual and lengthy process. But in the meantime, very old

patterns are rapidly reemerging: China reestablishing relations with ancient

tributary states from Korea to Vietnam, radical Islamists attempting to

reestablish their ancient role as the guardians of finance and piety at the

in the Central Asian caravan routes and across Indian Ocean, every sort of

Medieval trade diaspora reemerging… In the process, old political models

remerge as well: the Chinese principle of the state transcending law, the

Islamic principle of a legal order transcending any state. Everywhere, we

see the revival too of ancient forms of exploitation‹feudalism, slavery,

debt peonage‹often entangled in the newest forms of technology, but still

echoing all the worst abuses of the Middle Ages. A scramble for resources

has begun, with US occupation of Iraq and saber-rattling throughout the

surrounding region clearly meant (at least in part) to place a potential

stranglehold the energy supply of China; Chinese attempts to outflank with

its own scramble for Africa, with increasing forays into South America and

even Eastern Europe. The Chinese invasion into Africa (not as of yet at

least a military invasion, but already involving the movement of hundreds of

thousands of people), is changing the world in ways that will probably be

felt for centuries. Meanwhile, the nations of South America, the first

victims of the ‘Washington consensus’ have managed to largely wriggle free

from the US colonial orbit, while the US, its forces tied down in the Middle

East, has for the moment at least abandoned it, is desperately struggling to

keep its grip Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean‹its own ‘near

abroad’.

XIII

In another age all this might have led to war‹that is, not just colonial

occupations, police actions, or proxy wars (which are obviously already

taking place), but direct military confrontations between the armies of

major powers. It still could; accidents happen; but there is reason to

believe that, when it comes to moments of critical decision, the loyalties

of the global elites are increasingly to each other, and not to the national

entities for whom they claim to speak. There is some compelling evidence for

this.

Take for example when the US elites panicked at the prospect of the massive

budget surpluses of the late 1990s. As Alan Greenspan, head of the Federal

Reserve at the time warned, if these were allowed to stand they would have

flooded government coffers with so many trillions of dollars that it could

only have lead to some form of creeping socialism, even, he predicted, to

the government acquiring ‘equity stakes’ in key US corporations. The more

excitable of capitalism’s managers actually began contemplating scenarios

where the capitalist system itself would be imperiled. The only possible

solution was massive tax cuts; these were duly enacted, and did indeed

manage to turn surpluses into enormous deficits, financed by the sale of

treasury bonds to Japan and China. Conditions have thus now reached a point

where it is beginning to look as if the most likely long term outcome for

the US (its technological and industrial base decaying, sinking under the

burden of its enormous security spending) will be to end up serve as junior

partner and military enforcer for East Asia capital. Its rulers, or at least

a significant proportion of them, would prefer to hand global hegemony to

the rulers of China (provided the latter abandon Communism) than to return

to any sort of New Deal compromise with their ‘own’ working classes.

A second example lies in the origins of what has been called the current

‘Bretton Woods II’ system of currency arrangements, which underline a close

working together of some ‘surplus’ and ‘deficit’ countries within global

circuits. The macroeconomic manifestation of the planetary restructuring

outlined in XIX underlines both the huge US trade deficit that so much seem

to worry many commentators, and the possibility to continually generate new

debt instruments like the one that has recently resulted in the sub-prime

crisis. The ongoing recycling of accumulated surplus of countries exporting

to the USA such as China and oil producing countries is what has allowed

financiers to create new credit instruments in the USA. Hence, the ‘deal’

offered by the masters in the United States to its commoners has been this:

‘you, give us a relative social peace and accept capitalist markets as the

main means through which you reproduce your own livelihoods, and we will

give you access to cheaper consumption goods, access to credit for buying

cars and homes, and access to education, health, pensions and social

security through the speculative means of stock markets and housing prices.’

Similar compromises were reached in all the G8 countries.

Meanwhile, there is the problem of maintaining any sort of social peace with

the hundreds of millions of unemployed, underemployed, dispossessed

commoners currently swelling the shanty-towns of Asia, Africa, and Latin

America as a result of ongoing enclosures (which have speeded up within

China and India in particular, even as ‘structural adjustment policies’ in

Africa and Latin America have been derailed). Any prospect of maintaining

peace in these circumstances would ordinarily require either extremely high

rates of economic growth‹which globally have not been forthcoming, since

outside of China, growth rates in the developing world have been much lower

than they were in the ‘50s, ‘60s, or even ‘70s‹or extremely high levels of

repression, lest matters descend into rebellion or generalized civil war.

The latter has of course occurred in many parts of the world currently

neglected by capital, but in favored regions, such as the coastal provinces

of China, or ‘free trade’ zones of India, Egypt, or Mexico, commoners are

being offered a different sort of deal: industrial employment at wages that,

while very low by international standards, are still substantially higher

than anything currently obtainable in the impoverished countryside; and

above all the promise, through the intervention of Western markets and

(privatized) knowledge, of gradually improving conditions of living. While

over the least few years wages in many such areas seem to be growing, thanks

to the intensification of popular struggles, such gains are inherently

vulnerable: the effect of recent food inflation has been to cut real wages

back dramatically‹and threaten millions with starvation.

What we really want to stress here, though, is that the long-term promise

being offered to the South is just as untenable as the idea that US or

European consumers can indefinitely expand their conditions of life through

the use of mortgages and credit cards.

What’s being offered the new dispossessed is a transposition of the American

dream. The idea is that the lifestyle and consumption patterns of existing

Chinese, Indian, or Brazilian or Zambian urban middle classes (already

modeled on Northern ones) will eventually become available to the children

of today’s miners, maquila or plantation laborers, until, ultimately,

everyone on earth is brought up to roughly the same level of consumption.

Put in these terms, the argument is absurd. The idea that all six billion of

us can become ‘middle class’ is obviously impossible. First of all there is

a simple problem of resources. It doesn’t matter how many bottles we recycle

or how energy efficient are the light bulbs we use, there’s just no way the

earth’s ecosystem can accommodate six billion people driving in private cars

to work in air-conditioned cubicles before periodically flying off to

vacation in Acapulco or Tahiti. To maintain the style of living and

producing in common we now identify with ‘middle classness’ on a planetary

scale would require several additional planets.

This much has been pointed out repeatedly. But the second point is no less

important. What this vision of betterment ultimately proposes is that it

would be possible to build universal prosperity and human dignity on a

system of wage labor. This is fantasy. Historically, wages are always the

contractual face for system of command and degradation, and a means of

disguising exploitation: expressing value for work only on condition of

stealing value without work‹ and there is no reason to believe they could

ever be anything else. This is why, as history has also shown, human beings

will always avoid working for wages if they have any other viable option.

For a system based on wage labor to come into being, such options must

therefore be made unavailable. This in turn means that such systems are

always premised on structures of exclusion: on the prior existence of

borders and property regimes maintained by violence. Finally, historically,

it has always proved impossible to maintain any sizeable class of

wage-earners in relative prosperity without basing that prosperity, directly

or indirectly, on the unwaged labor of others‹on slave-labor, women’s

domestic labor, the forced labor of colonial subjects, the work of women and

men in peasant communities halfway around the world‹by people who are even

more systematically exploited, degraded, and immiserated. For that reason,

such systems have always depended not only on setting wage-earners against

each other by inciting bigotry, prejudice, hostility, resentment, violence,

but also by inciting the same between men and women, between the people of

different continents (“race”), between the generations.

From the perspective of the whole, then, the dream of universal middle class

‘betterment’ must necessarily be an illusion constructed in between the

Scylla of ecological disaster, and the Charybdis of poverty, detritus, and

hatred: precisely, the two pillars of today’s strategic impasse faced by the

G8.

XIV

How then do we describe the current impasse of capitalist governance?

To a large degree, it is the effect of a sudden and extremely effective

upswing of popular resistance‹one all the more extraordinary considering the

huge resources that had been invested in preventing such movements from

breaking out.

On the one hand, the turn of the millennium saw a vast and sudden flowering

of new anti-capitalist movements, a veritable planetary uprising against

neoliberalism by commoners in Latin America, India, Africa, Asia, across the

North Atlantic world’s former colonies and ultimately, within the cities of

the former colonial powers themselves. As a result, the neoliberal project

lies shattered. What came to be called the ‘anti-globalization’ movement

took aim at the trade bureaucracies‹the obvious weak link in the emerging

institutions of global administration‹but it was merely the most visible

aspect of this uprising. It was however an extraordinarily successful one.

Not only was the WTO halted in its tracks, but all major trade initiatives

(MAI, FTAAŠ) scuttled. The World Bank was hobbled and the power of the IMF

over most of the world’s population, effectively, destroyed. The latter,

once the terror of the Global South, is now a shattered remnant of its

former self, reduced to selling off its gold reserves and desperately

searching for a new global mission.

In many ways though spectacular street actions were merely the most visible

aspects of much broader changes: the resurgence of labor unions, in certain

parts of the world, the flowering of economic and social alternatives on the

grassroots levels in every part of the world, from new forms of direct

democracy of indigenous communities like El Alto in Bolivia or self-managed

factories in Paraguay, to township movements in South Africa, farming

cooperatives in India, squatters’ movements in Korea, experiments in

permaculture in Europe or ‘Islamic economics’ among the urban poor in the

Middle East. We have seen the development of thousands of forms of mutual

aid association, most of which have not even made it onto the radar of the

global media, often have almost no ideological unity and which may not even

be aware of each other’s existence, but nonetheless share a common desire to

mark a practical break with capitalism, and which, most importantly, hold

out the prospect of creating new forms of planetary commons that can‹and in

some cases are‹beginning to knit together to provide the outlines of genuine

alternative vision of what a non-capitalist future might look like.

The reaction of the world’s rulers was predictable. The planetary uprising

had occurred during a time when the global security apparatus was beginning

to look like it lacked a purpose, when the world threatened to return to a

state of peace. The response‹aided of course, by the intervention of some of

the US’ former Cold War allies, reorganized now under the name of Al

Qaeda‹was a return to global warfare. But this too failed. The ‘war on

terror’‹as an attempt to impose US military power as the ultimate enforcer

of the neoliberal model‹has collapsed as well in the face of almost

universal popular resistance. This is the nature of their ‘impasse’.

At the same time, the top-heavy, inefficient US model of military

capitalism‹a model created in large part to prevent the dangers of social

movements, but which the US has also sought to export to some degree simply

because of its profligacy and inefficiency, to prevent the rest of the world

from too rapidly overtaking them‹has proved so wasteful of resources that it

threatens to plunge the entire planet into ecological and social crisis.

Drought, disaster, famines, combine with endless campaigns of enclosure,

foreclosure, to cast the very means of survival‹food, water, shelter‹into

question for the bulk of the world’s population.

XV

In the rulers’ language the crisis understood, first and foremost, as a

problem of regulating cash flows, of reestablishing, as they like to put it,

a new ‘financial architecture’. Obviously they are aware of the broader

problems. Their promotional literature has always been full of it. From the

earliest days of the G7, through to the days after the Cold War, when Russia

was added as a reward for embracing capitalism, they have always claimed

that their chief concerns include

• the reduction of global poverty

• sustainable environmental policies

• sustainable global energy policies

• stable financial institutions governing global trade and currency

transactions

If one were to take such claims seriously, it’s hard to see their overall

performance as anything but a catastrophic failure. At the present moment,

all of these are in crisis mode: there are food riots, global warming, peak

oil, and the threat of financial meltdown, bursting of credit bubbles,

currency crises, a global credit crunch. [**Failure on this scale however,

opens opportunities for the G8 themselves, as summit of the global

bureaucracy, to reconfigure the strategic horizon. Therefore, it’s always

with the last of these that they are especially concerned. ]The real

problem, from the perspective of the G8, is one of reinvestment:

particularly, of the profits of the energy sector, but also, now, of

emerging industrial powers outside the circle of the G8 itself. The

neoliberal solution in the ‘70s had been to recycle OPEC’s petrodollars into

banks that would use it much of the world into debt bondage, imposing

regimes of fiscal austerity that, for the most part, stopped development

(and hence, the emergence potential rivals) in its tracks. By the ‘90s,

however, much East Asia in particular had broken free of this regime.

Attempts to reimpose IMF-style discipline during the Asian financial crisis

of 1997 largely backfired. So a new compromise was found, the so-called

Bretton Woods II: to recycle the profits from the rapidly expanding

industrial economies of East Asia into US treasury debt, artificially

supporting the value of the dollar and allowing a continual stream of cheap

exports that, aided by the US housing bubble, kept North Atlantic economies

afloat and buy off workers there with cheap oil and even cheaper consumer

goods even as real wages shrank. This solution however soon proved a

temporary expedient. Bush regime’s attempt to lock it in by the invasion of

Iraq, which was meant to lead to the forced privatization of Iraqi oil

fields, and, ultimately, of the global oil industry as a whole, collapsed in

the face of massive popular resistance (just as Saddam Hussein’s attempt to

introduce neoliberal reforms in Iraq had failed when he was still acting as

American deputy in the ‘90s). Instead, the simultaneous demand for petroleum

for both Chinese manufacturers and American consumers caused a dramatic

spike in the price of oil. What’s more, rents from oil and gas production

are now being used to pay off the old debts from the ‘80s (especially in

Asia and Latin America, which have by now paid back their IMF debts

entirely), and‹increasingly‹to create state-managed Sovereign Wealth Funds

that have largely replaced institutions like the IMF as the institutions

capable of making long-term strategic investments. The IMF, purposeless,

tottering on the brink of insolvency, has been reduced to trying to come up

with ‘best practices’ guidelines for fund managers working for governments

in Singapore, Seoul, and Abu Dhabi.

There can be no question this time around of freezing out countries like

China, India, or even Brazil. The question for capital’s planners, rather,

is how to channel these new concentrations of capital in such a way that

they reinforce the logic of the system instead of undermining it.

XVI

How can this be done? This is where appeals to universal human values, to

common membership in an ‘international community’ come in to play. ‘We all

must pull together for the good of the planet,’ we will be told. The money

must be reinvested ‘to save the earth.’

To some degree this was always the G8 line: this is a group has been making

an issue of climate change since 1983. Doing so was in one sense a response

to the environmental movements of the ‘70s and ‘80s. The resultant emphasis

on biofuels and ‘green energy’ was from their point of view, the perfect

strategy, seizing on an issue that seemed to transcend class, appropriating

ideas and issues that emerged from social movements (and hence coopting and

undermining especially their radical wings), and finally, ensuring such

initiatives are pursued not through any form of democratic self-organization

but ‘market mechanisms’‹to effective make the sense of public interest

productive for capitalism.

What we can expect now is a two-pronged attack. On the one hand, they will

use the crisis to attempt to reverse the gains of past social movements: to

put nuclear energy back on the table to deal with the energy crisis and

global warming, or genetically modified foods to deal with the food crisis.

Prime Minister Fukuda, the host of the current summit, for example, is

already proposing the nuclear power is the ‘solution’ to the global warming

crisis, even as the German delegation resists. On the other, and even more

insidiously, they will try once again to co-opt the ideas and solutions that

have emerged from our struggles as a way of ultimately undermining them.

Appropriating such ideas is simply what rulers do: the bosses brain is

always under the workers’ hat. But the ultimate aim is to answer the

intensification of class struggle, of the danger of new forms of democracy,

with another wave of enclosures, to restore a situation where commoners’

attempts to create broader regimes of cooperation are stymied, and people

are plunged back into mutual competition.

We can already see the outlines of how this might be done. There are already

suggestions that Sovereign Wealth Funds put aside a certain (miniscule)

proportion of their money for food aid, but only as tied to a larger project

of global financial restructuring. The World Bank, largely bereft of its

earlier role organizing dams and pipe-lines across the world, has been

funding development in China’s poorer provinces, freeing the Chinese

government to carry out similar projects in Southeast Asia, Africa, and even

Latin America (where, of course, they cannot effectively be held to any sort

of labor or environmental standards). There is the possibility of a new

class deal in China itself, whose workers can be allowed higher standards of

living if new low wage zones are created elsewhere‹for instance, Africa (the

continent where struggles over maintaining the commons have been most

intense in current decades)‹with the help of Chinese infrastructural

projects. Above of all, money will be channeled into addressing climate

change, into the development of alternative energy, which will require

enormous investments, in such a way as to ensure that whatever energy

resources do become important in this millennium, they can never be

democratized‹that the emerging notion of a petroleum commons, that energy

resources are to some degree a common patrimony meant primarily to serve the

community as a whole, that is beginning to develop in parts of the Middle

East and South America‹not be reproduced in whatever comes next.

Since this will ultimately have to be backed up by the threat of violence,

the G8 will inevitably have to struggle with how to (yet again) rethink

enforcement mechanisms. The latest move , now that the US ‘war on terror’

paradigm has obviously failed, would appear to be a return to NATO, part of

a reinvention of the ‘European security architecture’ being proposed at the

upcoming G8 meetings in Italy in 2009 on the 60th anniversary of NATO’s

foundation‹but part of a much broader movement of the militarization of

social conflict, projecting potential resource wars, demographic upheavals

resulting from climate change, and radical social movements as potential

military problems to be resolved by military means. Opposition to this new

project is already shaping up as the major new European mobilization for the

year following the current G-8.

XVII

While the G-8 sit at the pinnacle of a system of violence, their preferred

idiom is monetary. Their impulse whenever possible is to translate all

problems into money, financial structures, currency flows‹a substance whose

movements they carefully monitor and control.

Money, on might say, is their poetry‹a poetry whose letters are written in

our blood. It is their highest and most abstract form of expression, their

way of making statements about the ultimate truth of the world, even if it

operates in large part by making things disappear. How else could it be

possible to argue‹no, to assume as a matter of common sense‹that the love,

care, and concern of a person who tends to the needs of children, teaching,

minding, helping them to become decent , thoughtful, human beings, or who

grows and prepares food, is worth ten thousand times less than someone who

spends the same time designing a brand logo, moving abstract blips across a

globe, or denying others health care.

The role of money however has changed profoundly since 1971 when the dollar

was delinked from gold. This has created a profound realignment of temporal

horizons. Once money could be said to be primarily congealed results of past

profit and exploitation. As capital, it was dead labor. Millions of

indigenous Americans and Africans had their lives pillaged and destroyed in

the gold mines in order to be rendered into value. The logic of finance

capital, of credit structures, certainly always existed as well (it is at

least as old as industrial capital; possibly older), but in recent decades

these logic of financial capital has come to echo and re-echo on every level

of our lives. In the UK 97% of money in circulation is debt, in the US, 98%.

Governments run on deficit financing, wealthy economies on consumer debt,

the poor are enticed with microcredit schemes, debts are packaged and

repackaged in complex financial derivatives and traded back and forth. Debt

however is simply a promise, the expectation of future profit; capital thus

increasingly brings the future into the present‹a future that, it insists,

must always be the same in nature, even if must also be greater in

magnitude, since of course the entire system is premised on continual

growth. Where once financiers calculated and traded in the precise measure

of our degradation, having taken everything from us and turned it into

money, now money has flipped, to become the measure of our future

degradation‹at the same time as it binds us to endlessly working in the

present.

The result is a strange moral paradox. Love, loyalty, honor, commitment‹to

our families, for example, which means to our shared homes, which means to

the payment of monthly mortgage debts‹becomes a matter of maintaining

loyalty to a system which ultimately tells us that such commitments are not

a value in themselves. This organization of imaginative horizons, which

ultimately come down to a colonization of the very principle of hope, has

come to supplement the traditional evocation of fear (of penury,

homelessness, joblessness, disease and death). This colonization paralyzes

any thought of opposition to a system that almost everyone ultimately knows

is not only an insult to everything they really cherish, but a travesty of

genuine hope, since, because no system can really expand forever on a finite

planet, everyone is aware on some level that in the final analysis they are

dealing with a kind of global pyramid scheme, what we are ultimately buying

and selling is the real promise of global social and environmental

apocalypse.

XVIII

Finally then we come to the really difficult, strategic questions. Where are

the vulnerabilities? Where is hope? Obviously we have no certain answers

here. No one could. But perhaps the proceeding analysis opens up some

possibilities that anti-capitalist organizers might find useful to explore.

One thing that might be helpful is to rethink our initial terms. Consider

communism. We are used to thinking of it as a total system that perhaps

existed long ago, and to the desire to bring about an analogous system at

some point in the future‹usually, at whatever cost. It seems to us that

dreams of communist futures were never purely fantasies; they were simply

projections of existing forms of cooperation, of commoning, by which we

already make the world in the present. Communism in this sense is already

the basis of almost everything, what brings people and societies into being,

what maintains them, the elemental ground of all human thought and action.

There is absolutely nothing utopian here. What is utopian, really, is the

notion that any form of social organization, especially capitalism, could

ever exist that was not entirely premised on the prior existence of

communism. If this is true, the most pressing question is simply how to make

that power visible, to burst forth, to become the basis for strategic

visions, in the face of a tremendous and antagonistic power committed to

destroying it‹but at the same time, ensuring that despite the challenge they

face, they never again become entangled with forms of violence of their own

that make them the basis for yet another tawdry elite. After all, the

solidarity we extend to one another, is it not itself a form of communism?

And is it not so above because it is not coerced?

Another thing that might be helpful is to rethink our notion of crisis.

There was a time when simply describing the fact that capitalism was in a

state of crisis, driven by irreconcilable contradictions, was taken to

suggest that it was heading for a cliff. By now, it seems abundantly clear

that this is not the case. Capitalism is always in a crisis. The crisis

never goes away. Financial markets are always producing bubbles of one sort

or another; those bubbles always burst, sometimes catastrophically; often

entire national economies collapse, sometimes the global markets system

itself begins to come apart. But every time the structure is reassembled.

Slowly, painfully, dutifully, the pieces always end up being put back

together once again.

Perhaps we should be asking: why?

In searching for an answer, it seems to us, we might also do well to put

aside another familiar habit of radical thought: the tendency to sort the

world into separate levels‹material realities, the domain of ideas or

‘consciousness’, the level of technologies and organizations of

violence‹treating these as if these were separate domains that each work

according to separate logics, and then arguing which ‘determines’ which. In

fact they cannot be disentangled. A factory may be a physical thing, but the

ownership of a factory is a social relation, a legal fantasy that is based

partly on the belief that law exists, and partly on the existence of armies

and police. Armies and police on the other hand exist partly because of

factories providing them with guns, vehicles, and equipment, but also,

because those carrying the guns and riding in the vehicles believe they are

working for an abstract entity they call ‘the government’, which they love,

fear, and ultimately, whose existence they take for granted by a kind of

faith, since historically, those armed organizations tend to melt away

immediately the moment they lose faith that the government actually exists.

Obviously exactly the same can be said of money. It’s value is constantly

being produced by eminently material practices involving time clocks, bank

machines, mints, and transatlantic computer cables, not to mention love,

greed, and fear, but at the same time, all this too rests on a kind of faith

that all these things will continue to interact in more or less the same

way. It is all very material, but it also reflects a certain assumption of

eternity: the reason that the machine can always be placed back together is,

simply, because everyone assumes it must. This is because they cannot

realistically imagine plausible alternatives; they cannot imagine plausible

alternatives because of the extraordinarily sophisticated machinery of

preemptive violence that ensure any such alternatives are uprooted or

contained (even if that violence is itself organized around a fear that

itself rests on a similar form of faith.) One cannot even say it’s circular.

It’s more a kind of endless, unstable spiral. To subvert the system is then,

to intervene in such a way that the whole apparatus begins to spin apart.

XIX

It appears to us that one key element here‹one often neglected in

revolutionary strategy‹is the role of the global middle classes. This is a

class that, much though it varies from country (in places like the US and

Japan, overwhelming majorities consider themselves middle class; in, say,

Cambodia or Zambia, only very small percentages), almost everywhere provides

the key constituency of the G8 outside of the ruling elite themselves. It

has become a truism, an article of faith in itself in global policy circles,

that national middle class is everywhere the necessary basis for democracy.

In fact, middle classes are rarely much interested in democracy in any

meaningful sense of that word (that is, of the self-organization or

self-governance of communities). They tend to be quite suspicious of it.

Historically, middle classes have tended to encourage the establishment of

constitutional republics with only limited democratic elements (sometimes,

none at all). This is because their real passion is for a ‘betterment’, for

the prosperity and advance of conditions of life for their children‹and this

betterment, since it is as noted above entirely premised on structures of

exclusion, requires ‘security’. Actually the middle classes depend on

security on every level: personal security, social security (various forms

of government support, which even when it is withdrawn from the poor tends

to be maintained for the middle classes), security against any sudden or

dramatic changes in the nature of existing institutions. Thus, politically,

the middle classes are attached not to democracy (which, especially in its

radical forms, might disrupt all this), but to the rule of law. In the

political sense, then, being ‘middle class’ means existing outside the

notorious ‘state of exception’ to which the majority of the world’s people

are relegated. It means being able to see a policeman and feel safer, not

even more insecure. This would help explain why within the richest

countries, the overwhelming majority of the population will claim to be

‘middle class’ when speaking in the abstract, even if most will also

instantly switch back to calling themselves ‘working class’ when talking

about their relation to their boss.

That rule of law, in turn, allows them to live in that temporal horizon

where the market and other existing institutions (schools, governments, law

firms, real estate brokeragesŠ) can be imagined as lasting forever in more

or less the same form. The middle classes can thus be defined as those who

live in the eternity of capitalism. (The elites don’t; they live in history,

they don’t assume things will always be the same. The disenfranchized don’t;

they don’t have the luxury; they live in a state of precarity where little

or nothing can safely be assumed.) Their entire lives are based on assuming

that the institutional forms they are accustomed to will always be the same,

for themselves and their grandchildren, and their ‘betterment’ will be

proportional to the increase in the level of monetary wealth and

consumption. This is why every time global capital enters one of its

periodic crises, every time banks collapse, factories close, and markets

prove unworkable, or even, when the world collapses in war, the managers and

dentists will tend to support any program that guarantees the fragments will

be dutifully pieced back together in roughly the same form‹even if all are,

at the same time, burdened by at least a vague sense that the whole system

is unfair and probably heading for catastrophe.

XIX

The strategic question then is, how to shatter this sense of inevitability?

History provides one obvious suggestion. The last time the system really

neared self-destruction was in the 1930s, when what might have otherwise

been an ordinary turn of the boom-bust cycle turned into a depression so

profound that it took a world war to pull out of it. What was different? The

existence of an alternative: a Soviet economy that, whatever its obvious

brutalities, was expanding at breakneck pace at the very moment market

systems were undergoing collapse. Alternatives shatter the sense of

inevitability, that the system must, necessarily, be patched together in the

same form; this is why it becomes an absolute imperative of global

governance that even small viable experiments in other ways of organizing

communities be wiped out, or, if that is not possible, that no one knows

about them.

If nothing else, this explains the extraordinary importance attached to the

security services and preemption of popular struggle. Commoning, where it

already exists, must be made invisible. Alternatives‹ Zapatistas in Chiapas,

APPO in Oaxaca, worker-managed factories in Argentina or Paraguay,

community-run water systems in South Africa or Bolivia, living alternatives

of farming or fishing communities in India or Indonesia, or a thousand other

examples‹must be made to disappear, if not squelched or destroyed, then

marginalized to the point they seem irrelevant, ridiculous. If the managers

of the global system are so determined to do this they are willing to invest

such enormous resources into security apparatus that it threatens to sink

the system entirely, it is because they are aware that they are working with

a house of cards. That the principle of hope and expectation on which

capitalism rests would evaporate instantly if almost any other principle of

hope or expectation seemed viable.

The knowledge of alternatives, then, is itself a material force.

Without them, of course, the shattering of any sense of certainty has

exactly the opposite effect. It becomes pure precarity, an insecurity so

profound that it becomes impossible to project oneself in history in any

form, so that the one-time certainties of middle class life itself becomes a

kind of utopian horizon, a desperate dream, the only possible principle of

hope beyond which one cannot really imagine anything. At the moment, this

seems the favorite weapon of neoliberalism: whether promulgated through

economic violence, or the more direct, traditional kind.

One form of resistance that might prove quite useful here and is already

being discussed in some quarters are campaigns against debt itself. Not

demands for debt forgiveness, but campaigns of debt resistance.

XX

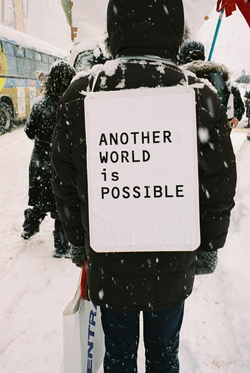

In this sense the great slogan of the global justice movement, ‘another

world is possible’, represents the ultimate threat to existing power

structures. But in another sense we can even say we have already begun to

move beyond that. Another world is not merely possible. It is inevitable. On

the one hand, as we have pointed out, such a world is already in existence

in the innumerable circuits of social cooperation and production in common

based on different values than those of profit and accumulation through

which we already create our lives, and without which capitalism itself would

be impossible. On the other, a different world is inevitable because

capitalism‹a system based on infinite material expansion‹simply cannot

continue forever on a finite world. At some point, if humanity is to survive

at all, we will be living in a system that is not based on infinite material

expansion. That is, something other than capitalism.

The problem is there is no absolute guarantee that ‘something’ will be any

better. It’s pretty easy to imagine ‘other worlds’ that would be even worse.

We really don’t have any idea what might happen. To what extent will the new

world still organized around commoditization of life, profit, and pervasive

competition? Or a reemergence of even older forms of hierarchy and

degradation? How, if we do overcome capitalism directly, by the building and

interweaving of new forms of global commons, do we protect ourselves against

the reemergence of new forms of hierarchy and division that we might not now

even be able to imagine?

It seems to us that the decisive battles that will decide the contours of

this new world will necessarily be battles around values. First and foremost

are values of solidarity among commoners. Since after all, every rape of a

woman by a man or the racist murder of an African immigrant by a European

worker is worth a division in capital’s army.

Similarly, imagining our struggles as value struggles might allow us to see

current struggles over global energy policies and over the role of money and

finance today as just an opening salvo of an even larger social conflict to

come. For instance, there’s no need to demonize petroleum, for example, as a

thing in itself. Energy products have always tended to play the role of a

‘basic good’, in the sense that their production and distribution becomes

the physical basis for all other forms of human cooperation, at the same

time as its control tends to organize social and even international

relations. Forests and wood played such a role from the time of the Magna

Carta to the American Revolution, sugar did so during the rise of European

colonial empires in the 17th and 18th centuries, fossil fuels do so today.

There is nothing intrinsically good or bad about fossil fuel. Oil is simply

solar radiation, once processed by living beings, now stored in fossil form.

The question is of control and distribution. This is the real flaw in the

rhetoric over ‘peak oil’: the entire argument is premised on the assumption

that, for the next century at least, global markets will be the only means

of distribution. Otherwise the use of oil would depend on needs, which would

be impossible to predict precisely because they depend on the form of

production in common we adopt. The question thus should be: how does the

anti-capitalist movement peak the oil? How does it become the crisis for a

system of unlimited expansion?

It is the view of the authors of this text that the most radical planetary

movements that have emerged to challenge the G8 are those that direct us

towards exactly these kind of questions. Those which go beyond merely asking

how to explode the role money plays in framing our horizons, or even

challenging the assumption of the endless expansion of ‘the economy’, to ask

why we assume something called ‘the economy’ even exists, and what other

ways we can begin imagining our material relations with one another. The

planetary women’s movement, in its many manifestations, has and continues to

play perhaps the most important role of all here, in calling for us to

reimagine our most basic assumptions about work, to remember that the basic

business of human life is not actually the production of communities but the

production, the mutual shaping of human beings. The most inspiring of these

movements are those that call for us to move beyond a mere challenge to the

role of money to reimagine value: to ask ourselves how can we best create a

situation where everyone is secure enough in their basic needs to be able to

pursue those forms of value they decide are ultimately important to them. To

move beyond a mere challenge to the tyranny of debt to ask ourselves what we

ultimately owe to one another and to our environment. That recognize that

none this needs to invented from whole cloth. It’s all already there,

immanent in the way everyone, as commoners, create the world together on a

daily basis. And that asking these questions is never, and can never be, an

abstract exercise, but is necessarily part of a process by which we are

already beginning to knit these forms of commons together into new forms of

global commons that will allow entirely new conceptions of our place in

history.

It is to those already engaged in such a project that we offer these initial

thoughts on our current strategic situation.